Test-Driving HTML Templates

- softscribble@gmail.com

- May 21, 2024

- Software development

- 0 Comments

After a decade or more where Single-Page-Applications generated by

JavaScript frameworks have

become the norm, we see that server-side rendered HTML is becoming

popular again, also thanks to libraries such as HTMX or Turbo. Writing a rich web UI in a

traditionally server-side language like Go or Java is now not just possible,

but a very attractive proposition.

We then face the problem of how to write automated tests for the HTML

parts of our web applications. While the JavaScript world has evolved powerful and sophisticated ways to test the UI,

ranging in size from unit-level to integration to end-to-end, in other

languages we do not have such a richness of tools available.

When writing a web application in Go or Java, HTML is commonly generated

through templates, which contain small fragments of logic. It is certainly

possible to test them indirectly through end-to-end tests, but those tests

are slow and expensive.

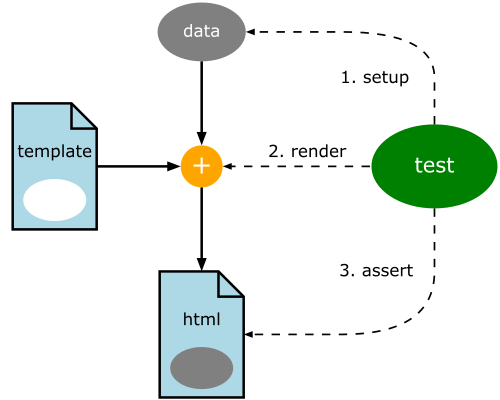

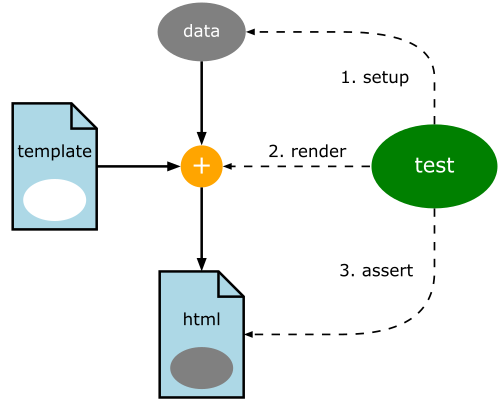

We can instead write unit tests that use CSS selectors to probe the

presence and correct content of specific HTML elements within a document.

Parameterizing these tests makes it easy to add new tests and to clearly

indicate what details each test is verifying. This approach works with any

language that has access to an HTML parsing library that supports CSS

selectors; examples are provided in Go and Java.

Motivation

Why test-drive HTML templates? After all, the most reliable way to check

that a template works is to render it to HTML and open it in a browser,

right?

There’s some truth in this; unit tests cannot prove that a template

works as expected when rendered in a browser, so checking them manually

is necessary. And if we make a

mistake in the logic of a template, usually the template breaks

in an obvious way, so the error is quickly spotted.

On the other hand:

- Relying on manual tests only is risky; what if we make a change that breaks

a template, and we don’t test it because we did not think it would impact the

template? We’d get an error at runtime! - Templates often contain logic, such as if-then-else’s or iterations over arrays of items,

and when the array is empty, we often need to show something different.

Manual checking all cases, for all of these bits of logic, becomes unsustainable very quickly - There are errors that are not visible in the browser. Browsers are extremely

tolerant of inconsistencies in HTML, relying on heuristics to fix our broken

HTML, but then we might get different results in different browsers, on different devices. It’s good

to check that the HTML structures we are building in our templates correspond to

what we think.

It turns out that test-driving HTML templates is easy; let’s see how to

do it in Go and Java. I will be using as a starting point the TodoMVC

template, which is a sample application used to showcase JavaScript

frameworks.

We will see techniques that can be applied to any programming language and templating technology, as long as we have

access to a suitable HTML parser.

This article is a bit long; you may want to take a look at the

final solution in Go or

in Java,

or jump to the conclusions.

Level 1: checking for sound HTML

The number one thing we want to check is that the HTML we produce is

basically sound. I don’t mean to check that HTML is valid according to the

W3C; it would be cool to do it, but it’s better to start with much simpler and faster checks.

For instance, we want our tests to

break if the template generates something like

<div>foo</p>

Let’s see how to do it in stages: we start with the following test that

tries to compile the template. In Go we use the standard html/template package.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

_ = templ

}

In Java, we use jmustache

because it’s very simple to use; Freemarker or

Velocity are other common choices.

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

}

If we run this test, it will fail, because the index.tmpl file does

not exist. So we create it, with the above broken HTML. Now the test should pass.

Then we create a model for the template to use. The application manages a todo-list, and

we can create a minimal model for demonstration purposes.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

model := todo.NewList()

_ = templ

_ = model

}

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var model = new TodoList();

}

Now we render the template, saving the results in a bytes buffer (Go) or as a String (Java).

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

model := todo.NewList()

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, model)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var model = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(model);

}

At this point, we want to parse the HTML and we expect to see an

error, because in our broken HTML there is a div element that

is closed by a p element. There is an HTML parser in the Go

standard library, but it is too lenient: if we run it on our broken HTML, we don’t get an

error. Luckily, the Go standard library also has an XML parser that can be

configured to parse HTML (thanks to this Stack Overflow answer)

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

model := todo.NewList()

// render the template into a buffer

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, model)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// check that the template can be parsed as (lenient) XML

decoder := xml.NewDecoder(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

decoder.Strict = false

decoder.AutoClose = xml.HTMLAutoClose

decoder.Entity = xml.HTMLEntity

for {

_, err := decoder.Token()

switch err {

case io.EOF:

return // We're done, it's valid!

case nil:

// do nothing

default:

t.Fatalf("Error parsing html: %s", err)

}

}

}

This code configures the HTML parser to have the right level of leniency

for HTML, and then parses the HTML token by token. Indeed, we see the error

message we wanted:

--- FAIL: Test_wellFormedHtml (0.00s)

index_template_test.go:61: Error parsing html: XML syntax error on line 4: unexpected end element </p>

In Java, a versatile library to use is jsoup:

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var model = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(model);

var parser = Parser.htmlParser().setTrackErrors(10);

Jsoup.parse(html, "", parser);

assertThat(parser.getErrors()).isEmpty();

}

And we see it fail:

java.lang.AssertionError: Expecting empty but was:<[<1:13>: Unexpected EndTag token [</p>] when in state [InBody],

Success! Now if we copy over the contents of the TodoMVC

template to our index.tmpl file, the test passes.

The test, however, is too verbose: we extract two helper functions, in

order to make the intention of the test clearer, and we get

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

model := todo.NewList()

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", model)

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

}

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var model = new TodoList();

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", model);

assertSoundHtml(html);

}

Contact Softscribble for your software Requirement

Contact Now